Safe Station: Audio Library

There, in New Bedford, the black man’s children—although anti-slavery was then far from popular—went to school side by side with the white children, and apparently without objection from any quarter. To make me at home, Mr. Johnson assured me that no slaveholder could take a slave from New Bedford; that there were men there who would lay down their lives, before such an outrage could be perpetrated. The colored people themselves were of the best metal, and would fight for liberty to the death.”

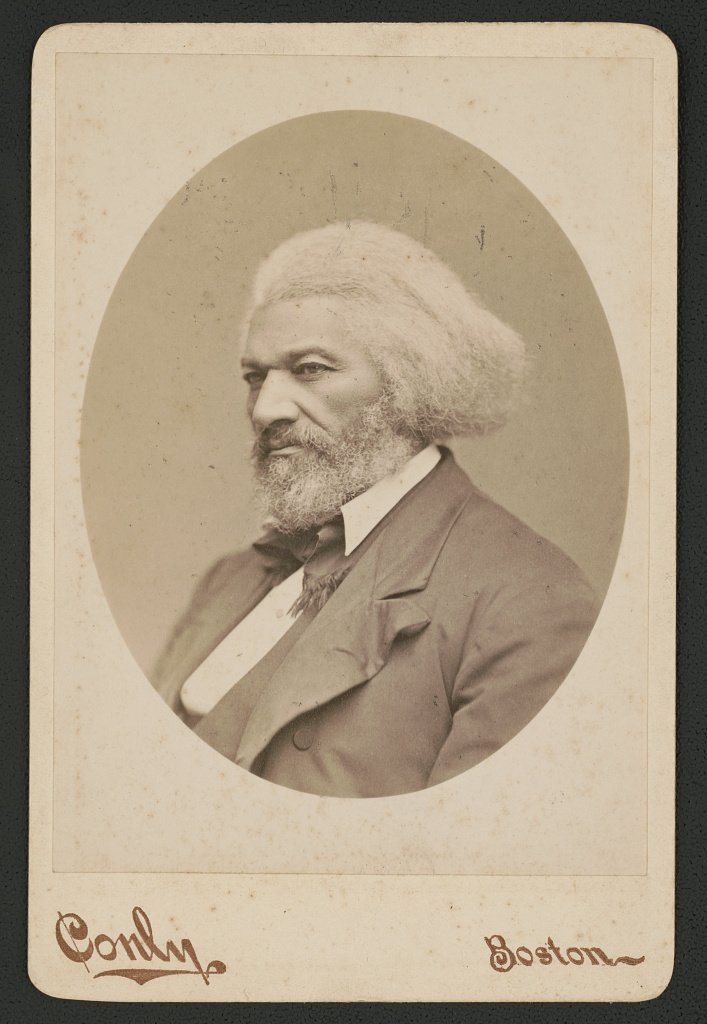

—Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855)

“Upon reaching New Bedford, we were directed to the house of Mr. Nathan Johnson, by whom we were kindly received, and hospitably provided for. Both Mr. and Mrs. Johnson took a deep and lively interest in our welfare. They proved themselves quite worthy of the name abolitionists…. We now began to feel a degree of safety, and to prepare ourselves for the duties and responsibilities of a life of freedom….

— Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845)

“I found employment, the third day after my arrival, in stowing a sloop with a load of oil. It was new, dirty, and hard work for me; but I went at it with a glad heart and a willing hand. I was now my own master. It was a happy moment, the rapture of which can be understood only by those who have been slaves. It was the first work, the reward of which was to be entirely my own. There was no Master Hugh standing ready, the moment I earned the money, to rob me of it. I worked that day with a pleasure I had never before experienced. I was at work for myself and newly-married wife. It was to me the starting-point of a new existence.”

—Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, 1845

“A wealthy Friend (Quaker) of New Bedford, writes to a friend of ours who enquired of him whether a fugitive slave would be safe in that city. ‘I profess to be a free soiler and hold to the ‘high law.’ God helping I mean to obey that. Therefore send along the ‘good likely’ fugitive, and if he is hungry we will feed him, if naked clothe him. He will be safe here. We have about 700 fugitives here in this city, and they are good citizens, and here we intend they shall stay.”

—“A City of Refuge,” Boston Chronotype, November 1850

Deborah Weston, New Bedford, to her sister Maria Weston Chapman, 12 April 1837

“I have postponed answering your letter concerning the coloured woman, from day to day in hopes that I should have something satisfactory to write at last, but I am constrained to say that I think a school here would have no sort of a chance for success. To me it is hardly desirable that there should be an exclusively coloured school established, for the public schools are all open, and black children admitted on terms of the most perfect equality.”

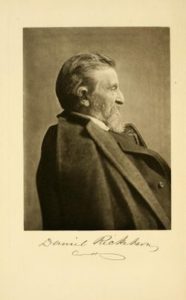

“In New Bedford I found a very kind and gentle friend in Daniel Ricketson. He lives in a beautiful place about a mile from the city. A man of taste, refinement, and wealth. He gave one hundred dollars towards purchasing a home for W.L. Garrison. He is a correspondent and ardent admirer of William and Mary Howitt. They have just sent him Mary’s picture engraved and William’s daguerreotype, both accounted very good likenesses. He is full of love for all the old English poets: writes himself for Edmund Quincy’s Liberty Bell. … I assure you it was a great pleasure to me to find such a gentleman abolitionist, with so much order, neatness, and good care in his home.”

– Sallie Holley, Letter To Miss Putnam, Island of Nantucket, Sept 30, 1852

“‘Polly’ . . . was a fair mulatto, always lady-like and pleasant. I remember of seeing her walking arm in arm with Mrs. Maria Weston Chapman, down Summer street, Boston, after an antislavery meeting a short time before the war, while I had the honor of escorting the venerable Lucretia Mott.”

—“Daniel Ricketson .,” New Bedford Daily Mercury, 6 October 1880

“My earliest remembrance of him [Nathan Johnson] goes back somewhat over forty years, when he and his worthy wife, ‘Polly,’ were the sine qua non at all the fashionable parties of our place, as caterers and waiters.”

—“Daniel Ricketson,” New Bedford Daily Mercury, 6 October 1880

“I waited until the captain went down below to dress for going ashore, and then I made a dash for liberty… when the ship tied up at the wharf at the foot of Union Street… I was over the edge and in the midst of an excited crowd. ‘A fugitive, a fugitive,’ was the cry as I sprung ashore… Had never heard the word ‘fugitive’ before and was pretty well scared out of my wits. But a slave had little to fear in a New Bedford crowd in slavery days… they stood aside and let me pass.”

— Joseph M. Smith, self-emancipated from North Carolina in 1830, Quote from a 1911 recollection

“In New Bedford I passed under the appellation of ‘fugitive’ which at once commanded the sympathy of that patriotic and generous people, and of whom it would seem unless that I should mention a single word after saying what, perhaps most readers know, —that this locality had always been considered the fugitive’s Gibraltar—a truth which puts poetry and fiction to blush; as I had been there but a short while when, acting as without the intervention of reason or deliberation its good citizens gathered around me with charitable offerings and a protest of eternal hatred to slavery and all its alliances…

— George Teamoh, who escaped from Norfolk, Virginia, on arriving to New Bedford

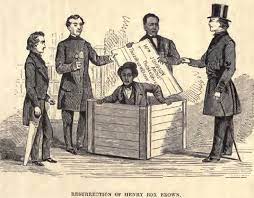

“Sarah & I went to [William] J Rotchs’ to tea but came home early—I there heard a singular account of the escape of a slave who had just arrived here which I must record—He had himself packed up in a box about 3 ft 2 in long- 2 ft 6 in wide & 1 ft 11 in deep and sent on by express from Richmond to Philadelphia—marked ‘this side up’— He is about 5 ft 6 in hight and weights about 200lb—In his way he came by cars & steam boat to [Philadelphia] near 25 hours in the box which was quite close & tight had only a bladder of water with him and kept himself alive by bathing his face and fanning himself with his hat. He was twice turned head downwards & once remained so on board the steam boat while she went 18 miles—which almost killed him and he said the veins on his temples were almost as thick as his finger. Yet he endured it all and was delivered to his antislavery friends safe & well—who trembled when he knocked on the box and asked the question ‘all right[‘]—and the answer came promptly ‘all right sir’—I think I never heard of an instance of greater fortitude & daring and he has well earned the freedom which he will now enjoy.” (27)

— Charles W. Morgan, 4 April 1849 Diary, after attending party at the home of William J. Rotch; recounting the tale of Henry Box Brown’s journey to freedom

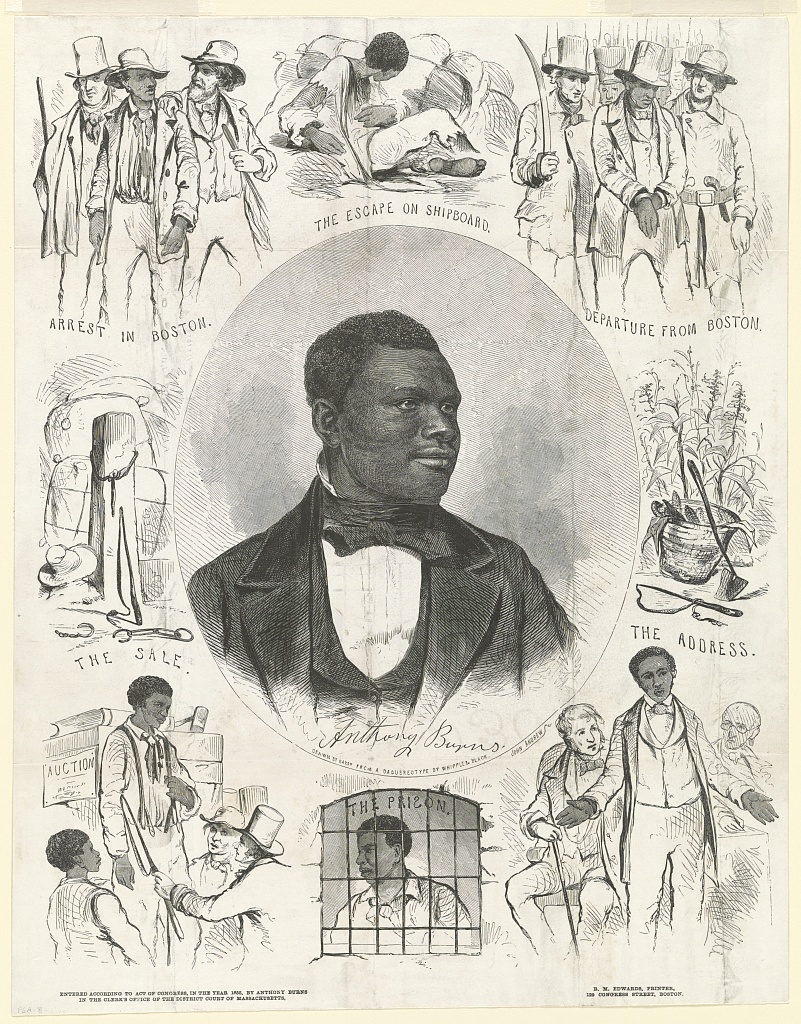

“Boston has been desecrated by the trade of the slave hunters. Boston has been humbled by the slave power. Boston is disgraced by the transactions of her own citizens, in the Simms and Burns’ tragedies. Shall New Bedford be everlastingly disgraced by following in the footsteps of so humiliating an example? . . . Is there a Court-house here, that can be turned into a slave pen? Is there a building here, that can be obtained for the purpose of imprisoning a human being, claimed as a slave? . . . Shall it ever be recorded upon the pages of our history, that a slave hunt was successful in New Bedford? God forbid.”

—New Bedford Republican Standard, 15 June 1854 (upon the rendition of Anthony Burns in Boston)

“It was a solemn & sad day for Boston—the Fugitive slave was remanded to slavery—The city was full of soldiers—the court house guarded with artillery—and hundreds of troops U States & volunteers . . . every where bayonets bristled— Thousands of people thronged the borders of the proscribed district & waited for hours to see the execution as they called it….. The people all seem to think alike and the general feeling is that there shall never again be such a scene be the consequences what they may–Let the slave hunters look out, for all the people are now incensed.”

—Diary of Charles W. Morgan, New Bedford, on the return of fugitive Anthony Burns to slavery, 2 June 1854

“The fugitive slaves and free negroes here, needed no word of mine to excite them to resist ‘the taking away runaway slaves.’ One of our Judges of the Court of Common Pleas said to a fugitive who asked him for money to enable him to go to Canada, No! Not a dollar, but if you want a ‘six barrel Pistol’ to defend your liberty on Massachusetts soil, and will promise to use it if necessary, I will give it to you, and any other arms you may require.’”

—Rodney French of New Bedford, “ Reply to a Portion of the Citizens of Newbern, in Council,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, 20 November 1851

“I have in the 54th Regt. my Husband, two cousins, and no less than seven young men that I have taught at Sabbath school, these with the three young men who boarded with my Father, is all very near to me, and it makes my heard bleed when I think of them with so many others, suffering for what I could do for them, if I was only permitted to do so. . . . I am anxious to do all that I can for them, and my country also. . . . What I want is to be useful.”

—Martha Bush Gray in a letter to her congressman, 1863, African American Civil War nurse who served the troops of the 54th and 55th Massachusetts

Thank you to Our Sisters’ School teachers, Tobey Eugenio and Emma York, for their participation and partnership. Special thanks to the New Bedford Historical Society for their support in creating this audio library.

Events

Community Volunteer Day

Join us in our last stages of creating a community-made public art piece celebrating Pride in SouthCoast Massachusetts. We’re calling on community members to help us bring Being Seen to life! Whether you’re into painting, crafting, organizing, or just want to lend a hand, there’s something for everyone. ✂️ Materials Provided – Paint, fabric, collage supplies & more (while they