New Bedford Then and Now: A Legacy of Belonging

This series features seven young artists from Our Sisters’ School who explore their city’s long-standing tradition of providing shelter for those in need and the ways that legacy lives on today. Through mixed-media artworks, including painting, drawing, and digital design, these artists examine the ways New Bedford has welcomed people – including people escaping slavery, refugees and immigrants pushed from their home countries, and people in the LGBTQ+ community.

These artworks — inspired by New Bedford’s Underground Railroad and abolitionist history — are accompanied by an audio library of quotes and stories from self-emancipated people who once called this city their home, read by Our Sisters’ School students.

Special thanks to the New Bedford Historical Society for their support in creating this audio library.

Thank you to Our Sisters’ School teachers, Tobey Eugenio and Emma York, for their participation and partnership.

Learn more about OSS at www.oursistersschool.org

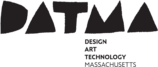

Finding Peace and Hope by Attyanna Timas

7th Grade, Oil and Acrylic Painting

“This piece represents the hurricane barrier in the South End of New Bedford and a mural with the word “Hope” in the center. I chose to paint the hurricane barrier because it connects different places in the South End and keeps New Bedford safe. I look at it as a symbol of peace and tranquility. The hurricane barrier blocks large waves from flooding the city and allows people to walk and ride bikes along the trail. I decided to add a mural of my own to the hurricane barrier to illustrate the way that hope connects New Bedford’s past to its present. As part of the Underground Railroad, New Bedford created safe houses for people escaping slavery and to this day New Bedford continues to provide hope for immigrants and refugees who have joined our community and contributed to the fishing industry and created the Madeira feast.”Attyanna Timas

Nuestra Mesa – Pernil, pasteles, plátanos y pastelillos by Daishaly Rodriguez

7th Grade, Pencil drawing

“I was inspired by how so many people let people escaping slavery into their homes and treated them like family. It led me to think of my own family who have been my support system. I eventually landed on the idea of having my family sitting around a table inviting the viewer and others seeking love in. I used the perspective of the artwork to my advantage in order to show how the newcomer might feel, and what they might see, when being welcomed into my family. I left some blank space at the table to show the importance of making space for others to join you. I wanted to build off of the idea of “who has a seat at the table” when decisions are being made about our community. It connects to the idea of inclusivity and who your chosen family is. My main goal is for the audience to understand that it is important to have our own support system but also to find a way to invite others into your community. I believe shelter is a place where you feel comfortable around people who love you.”

Connecting For Change by Aliana Paquette

5th Grade, Acrylic

“In my piece, I chose to paint the Black Lives Matter mural on Union Street: an iconic, inclusive space in downtown New Bedford. I wanted to convey how this space makes me, and others in my community, feel welcome. I believe that when murals are painted in our community, it does so much more than just add beauty – it sends the message that the city cares about that neighborhood and sees the people in it as worthy of representing. I believe that art has the power to build understanding across differences and in my piece I tried to do that by portraying a diverse group of young people who believe that Black Lives Matter. The artistic style generates a strong sense of simplicity of energy allowing the viewer to sense the comradery between the humans present in the pieces and the future humans who will visit. As you view this piece, I hope you too feel joyful and empowered to connect with others to work for positive change in your community.”

The Diversity of Acushnet Ave by Giovanna Peixoto

7th Grade, Digital Design with Procreate®

“My piece signifies an important street in New Bedford called Acushnet Ave. New Bedford is one of the first places people thought of when trying to find shelter during the trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and more recent refugee crises and, because of that, New Bedford became such a diverse city where people can shine their light however they want to. I wanted to show my viewers the diversity of my city and this street was my key. Everytime I pass by this street I see a variety of cultures being celebrated and people with different identities mingling at small businesses and family-owned restaurants that take pride in their roots. In this city, there is meaning everywhere you look, not only in what you can see. I wanted to represent the deeper meaning being one street in New Bedford as a way to illustrate the power of New Bedford’s diverse history. What’s beautiful to me about my city is that it is a place we can all call home.”

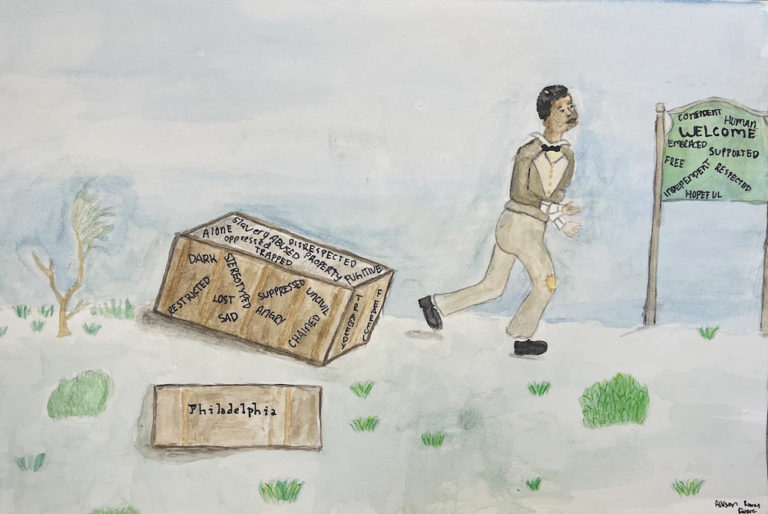

The Boxes We Live In by Allison Rivas Rivera

7th Grade, Watercolor

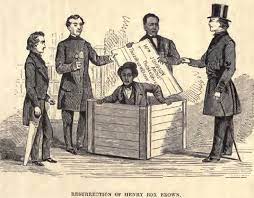

“The inspiration for my artwork was the story of Henry Box Brown who escaped from slavery by shipping himself North in a box. He traveled for 27 hours in a box that was only 3-feet and 1-inch long, 2-feet and 6-inches high, 2-feet wide, and had three holes for air. He eventually made it to Philadelphia and then, ultimately, to Joseph Ricketson in New Bedford. To me, that box represented the ways Henry Box Brown was trapped by slavery. Once he finally reached New Bedford, and broke free of that box, he was able to feel a new sense of possibility. I relate to the feeling of being enclosed in a box because for a long time I felt like I would never find a place or a person who could finally accept me for who I am. But once I found my people in the New Bedford community, I finally felt like me again. I imagine that feeling of coming back to yourself is what Henry Box Brown must have felt when he emerged from the box. I chose to put negative words inside the box because I wanted people to not just see, but feel, what enslaved people – and anyone who feels out of place in their community – went through or continues to go through just for being themselves. I chose to put positive words on the welcome sign for the city of New Bedford to show people that there is a place for them here, in this world and in New Bedford.”

Threads of Hope: Past and Present by Hannah Clark

7th Grade, Posca Paint Markers and Sharpies

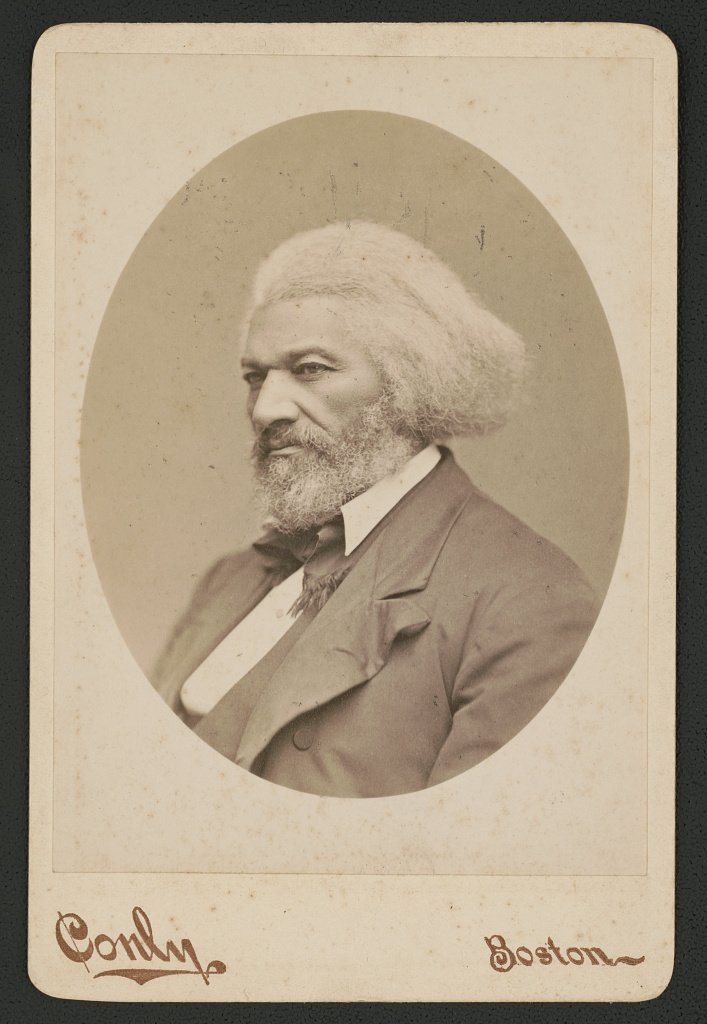

“We learned that in the 1800s abolitionists would weave maps into quilts to help people escape slavery and place quilts with particular stitching outside of safe houses to indicate that they were part of the Underground Railroad. That inspired me to create my first piece which represents the Nathan and Polly Johnson house on 7th Street. Nathan and Polly Johnson were local abolitionists who created a safe space for people – like Frederick Douglass – who were escaping slavery. My second piece is a shop in downtown New Bedford, with a pride flag hanging outside its window. A pride flag symbolizes a place that is safe for a person who is part of the LGBTQ+ community. My goal was to show how in two different periods of American history we created a safe and inclusive space for people who had been excluded in our community. I chose to make the house and shops in duller tones, so that the quilt and the pride flag really popped. I wanted the focus of my piece to be on those symbols of safety past and present.”

A Welcoming Hand by Mya Hachem

6th Grade, Digital Design with Procreate®

“This image was inspired by the story of Joseph M. Smith who escaped from slavery when he was only 19. He got on a lumber ship and traveled North. Once he reached New Bedford he jumped off of the ship and was welcomed with open arms by a crowd at the base of Union St. What I found most interesting about his story was that instead of pushing him back onto the boat and returning him to slavery – as the law required at the time – the people of New Bedford cleared a path for him to walk up Union Street to safety. They gave him food, water, and a place to stay. I hope that as a community we continue to do what is right, even when it isn’t popular or easy. I made the choice to change Joseph’s gender so that girls could also relate to his story.”

There, in New Bedford, the black man’s children—although anti-slavery was then far from popular—went to school side by side with the white children, and apparently without objection from any quarter. To make me at home, Mr. Johnson assured me that no slaveholder could take a slave from New Bedford; that there were men there who would lay down their lives, before such an outrage could be perpetrated. The colored people themselves were of the best metal, and would fight for liberty to the death.”

—Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855)

“Upon reaching New Bedford, we were directed to the house of Mr. Nathan Johnson, by whom we were kindly received, and hospitably provided for. Both Mr. and Mrs. Johnson took a deep and lively interest in our welfare. They proved themselves quite worthy of the name abolitionists…. We now began to feel a degree of safety, and to prepare ourselves for the duties and responsibilities of a life of freedom….

— Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845)

“I found employment, the third day after my arrival, in stowing a sloop with a load of oil. It was new, dirty, and hard work for me; but I went at it with a glad heart and a willing hand. I was now my own master. It was a happy moment, the rapture of which can be understood only by those who have been slaves. It was the first work, the reward of which was to be entirely my own. There was no Master Hugh standing ready, the moment I earned the money, to rob me of it. I worked that day with a pleasure I had never before experienced. I was at work for myself and newly-married wife. It was to me the starting-point of a new existence.”

—Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, 1845

“A wealthy Friend (Quaker) of New Bedford, writes to a friend of ours who enquired of him whether a fugitive slave would be safe in that city. ‘I profess to be a free soiler and hold to the ‘high law.’ God helping I mean to obey that. Therefore send along the ‘good likely’ fugitive, and if he is hungry we will feed him, if naked clothe him. He will be safe here. We have about 700 fugitives here in this city, and they are good citizens, and here we intend they shall stay.”

—“A City of Refuge,” Boston Chronotype, November 1850

Deborah Weston, New Bedford, to her sister Maria Weston Chapman, 12 April 1837

“I have postponed answering your letter concerning the coloured woman, from day to day in hopes that I should have something satisfactory to write at last, but I am constrained to say that I think a school here would have no sort of a chance for success. To me it is hardly desirable that there should be an exclusively coloured school established, for the public schools are all open, and black children admitted on terms of the most perfect equality.”

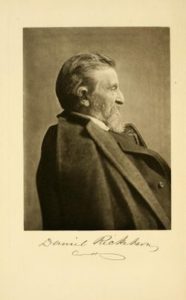

“In New Bedford I found a very kind and gentle friend in Daniel Ricketson. He lives in a beautiful place about a mile from the city. A man of taste, refinement, and wealth. He gave one hundred dollars towards purchasing a home for W.L. Garrison. He is a correspondent and ardent admirer of William and Mary Howitt. They have just sent him Mary’s picture engraved and William’s daguerreotype, both accounted very good likenesses. He is full of love for all the old English poets: writes himself for Edmund Quincy’s Liberty Bell. … I assure you it was a great pleasure to me to find such a gentleman abolitionist, with so much order, neatness, and good care in his home.”

– Sallie Holley, Letter To Miss Putnam, Island of Nantucket, Sept 30, 1852

“‘Polly’ . . . was a fair mulatto, always lady-like and pleasant. I remember of seeing her walking arm in arm with Mrs. Maria Weston Chapman, down Summer street, Boston, after an antislavery meeting a short time before the war, while I had the honor of escorting the venerable Lucretia Mott.”

—“Daniel Ricketson .,” New Bedford Daily Mercury, 6 October 1880

“My earliest remembrance of him [Nathan Johnson] goes back somewhat over forty years, when he and his worthy wife, ‘Polly,’ were the sine qua non at all the fashionable parties of our place, as caterers and waiters.”

—“Daniel Ricketson,” New Bedford Daily Mercury, 6 October 1880

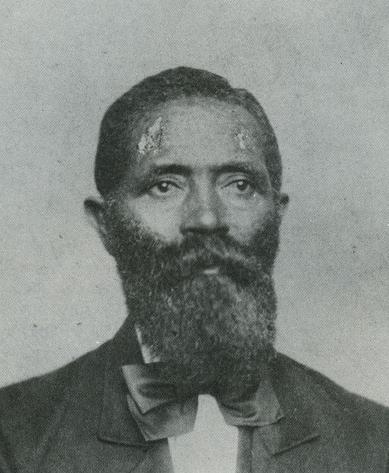

“I waited until the captain went down below to dress for going ashore, and then I made a dash for liberty… when the ship tied up at the wharf at the foot of Union Street… I was over the edge and in the midst of an excited crowd. ‘A fugitive, a fugitive,’ was the cry as I sprung ashore… Had never heard the word ‘fugitive’ before and was pretty well scared out of my wits. But a slave had little to fear in a New Bedford crowd in slavery days… they stood aside and let me pass.”

— Joseph M. Smith, self-emancipated from North Carolina in 1830, Quote from a 1911 recollection

“In New Bedford I passed under the appellation of ‘fugitive’ which at once commanded the sympathy of that patriotic and generous people, and of whom it would seem unless that I should mention a single word after saying what, perhaps most readers know, —that this locality had always been considered the fugitive’s Gibraltar—a truth which puts poetry and fiction to blush; as I had been there but a short while when, acting as without the intervention of reason or deliberation its good citizens gathered around me with charitable offerings and a protest of eternal hatred to slavery and all its alliances…

— George Teamoh, who escaped from Norfolk, Virginia, on arriving to New Bedford

“Sarah & I went to [William] J Rotchs’ to tea but came home early—I there heard a singular account of the escape of a slave who had just arrived here which I must record—He had himself packed up in a box about 3 ft 2 in long- 2 ft 6 in wide & 1 ft 11 in deep and sent on by express from Richmond to Philadelphia—marked ‘this side up’— He is about 5 ft 6 in hight and weights about 200lb—In his way he came by cars & steam boat to [Philadelphia] near 25 hours in the box which was quite close & tight had only a bladder of water with him and kept himself alive by bathing his face and fanning himself with his hat. He was twice turned head downwards & once remained so on board the steam boat while she went 18 miles—which almost killed him and he said the veins on his temples were almost as thick as his finger. Yet he endured it all and was delivered to his antislavery friends safe & well—who trembled when he knocked on the box and asked the question ‘all right[‘]—and the answer came promptly ‘all right sir’—I think I never heard of an instance of greater fortitude & daring and he has well earned the freedom which he will now enjoy.” (27)

— Charles W. Morgan, 4 April 1849 Diary, after attending party at the home of William J. Rotch; recounting the tale of Henry Box Brown’s journey to freedom

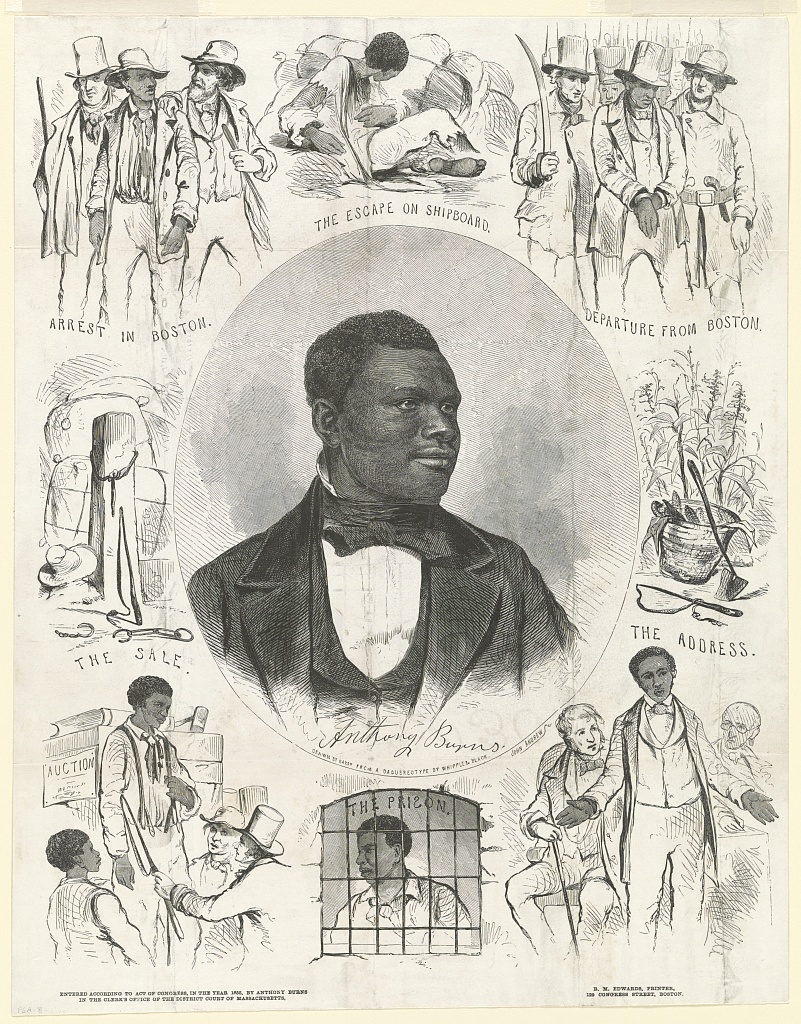

“Boston has been desecrated by the trade of the slave hunters. Boston has been humbled by the slave power. Boston is disgraced by the transactions of her own citizens, in the Simms and Burns’ tragedies. Shall New Bedford be everlastingly disgraced by following in the footsteps of so humiliating an example? . . . Is there a Court-house here, that can be turned into a slave pen? Is there a building here, that can be obtained for the purpose of imprisoning a human being, claimed as a slave? . . . Shall it ever be recorded upon the pages of our history, that a slave hunt was successful in New Bedford? God forbid.”

—New Bedford Republican Standard, 15 June 1854 (upon the rendition of Anthony Burns in Boston)

“It was a solemn & sad day for Boston—the Fugitive slave was remanded to slavery—The city was full of soldiers—the court house guarded with artillery—and hundreds of troops U States & volunteers . . . every where bayonets bristled— Thousands of people thronged the borders of the proscribed district & waited for hours to see the execution as they called it….. The people all seem to think alike and the general feeling is that there shall never again be such a scene be the consequences what they may–Let the slave hunters look out, for all the people are now incensed.”

—Diary of Charles W. Morgan, New Bedford, on the return of fugitive Anthony Burns to slavery, 2 June 1854

“The fugitive slaves and free negroes here, needed no word of mine to excite them to resist ‘the taking away runaway slaves.’ One of our Judges of the Court of Common Pleas said to a fugitive who asked him for money to enable him to go to Canada, No! Not a dollar, but if you want a ‘six barrel Pistol’ to defend your liberty on Massachusetts soil, and will promise to use it if necessary, I will give it to you, and any other arms you may require.’”

—Rodney French of New Bedford, “ Reply to a Portion of the Citizens of Newbern, in Council,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, 20 November 1851

“I have in the 54th Regt. my Husband, two cousins, and no less than seven young men that I have taught at Sabbath school, these with the three young men who boarded with my Father, is all very near to me, and it makes my heard bleed when I think of them with so many others, suffering for what I could do for them, if I was only permitted to do so. . . . I am anxious to do all that I can for them, and my country also. . . . What I want is to be useful.”

—Martha Bush Gray in a letter to her congressman, 1863, African American Civil War nurse who served the troops of the 54th and 55th Massachusetts

Events

Public Art Curator’s Tour

Public Art Curator’s Tour 4:30 – 5:15pm Take a walk through the culturally rich historic downtown New Bedford to view 4 contemporary sculptures, including a new interactive AI sculpture by architect & designer, Mona Ghandi, called “Mood-Vironment.” This public art trail led by Executive Director, Lindsay Mis will cover approximately 1 mile of walking. Tour